Anyone who has flown out of, or driven by, Essex County Airport on Passaic Avenue in Fairfield has probably assumed that the airport was conceived by local public officials. After all, before it was named for the county, it was also known as Caldwell Airport. Thanks, however, to the sleuthing of former Montclair resident, Alex Davidson, the early history of the airport, which is 80 years old, is now known. Surprisingly the airport, nearly 7 miles from town, was conceived to be an airport for Montclair residents.

This discovery begins with the recent decision of Joanne Davidson to sell the house at 383 Park Street where she and Alex's uncle Al had resided for decades before his death three years ago. While cleaning out the home to prepare it for sale, Alex came across a treasure trove in the basement and attic.

One part of the trove was a scrapbook with photos from his grandfather, Benjamin Palmer (B. P.) Davidson, the Newark Star-Eagle's "Today in Aviation" editor. He is the same individual who had rescued an eagle statue from destruction when a Newark Post Office building was torn down in 1938, then kept it in the Park Street house's backyard until the eagle was returned by the family to Newark for an unveiling in March 2002 only to be beheaded by a deranged young man in 2003. It has since been restored.

Among B. P. Davidson's photos was a picture of Charles Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis with the engine hoisted above it for overhaul at Teterboro Airport. The photo was taken upon Lucky Lindy's return from his first successful transatlantic flight. Alex soon realized that the photo was so rare that he offered it to the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, which eagerly accepted the one-of-a-kind photo.

In researching the photo at the Passaic County Historical Library, housed at Lambert Castle out Valley Road in Paterson, Alex came across a telegram expressing Lindbergh's thanks for how well the Wright engine performed during the famed flight. Alex's father, Ben, had mentioned that Alex's grandfather, B. P., often wrote about the airport in Caldwell, so Alex began looking for articles written by him. Shortly thereafter, Alex discovered that the airport, which later became Caldwell Airport and then Essex County Airport, was originally known as Curtiss Marvin Airport in 1929.

When he asked Fairfield area historians why it was known as Marvin, no one knew or even recollected that name. Most people remembered it as Essex Airport Curtiss-Wright Field, Caldwell, New Jersey which is how the U.S. Department of Commerce, Aeronautics Branch, referred to it in an August 13, 1930 Airway Bulletin. Curtiss-Wright had been a major employer in the area, but the airport history had been all but lost, a concept that bothered Alex who had learned to fly there in the 1960s as a teenager.

Soon Alex was at the Newark Library, where he found a 1970 obituary for Walter Sands Marvin, a stockbroker and banker, who had been president of Curtiss Airports Corporation and a founding director, with Charles Lindbergh, of Transcontinental Air Transport Company (T.A.T.), predecessor to TWA. In an amazing coincidence, the Brooklyn-born Marvin had moved to Montclair in 1919.

This led to the second part of the Park Street treasure trove: hard-bound volumes of The Montclair Times from 1900 to 1940, a period in which The Montclair Times was published twice a week filled with social notes about the comings and goings and social activities of area residents in Montclair and the North End, a term the Times changed in the late 1920s to Upper Montclair.

Alex and his family had donated these volumes to the Montclair Library, when they emptied the house, with the stipulation that the family be allowed to use them for research. Thus, down to the Montclair Library he went, weekend after weekend, with two assistants. One was David Cannon, a town resident since 1958 who grew up nearby at 412 Park Street and had done extensive research at the library in 1976. Later as a copywriter for Block Advertising, he wrote the positioning slogan that the Library used for many years on stationery: "Wisdom from the past, information about today, knowledge for tomorrow."

The other assistant was Phyllis Mariani of Tiffany & Co. who also wanted to scan the old newspapers because she was interested in learning more about the largest freshwater pearl which had been found either in Paterson's Third River or in Montclair's Toney's Brook depending on what one read. Paterson in maps from the 1800s had abutted Montclair. The pearl was eventually crafted by Tiffany & Co. into a crown worn by Princess Eugenia when she married Napoleon III.

Alex's research team meticulously searched each issue for news of the airport opening and finally found the Rosetta stone: An April 20, 1929 article announcing that a group of seven men, most from Montclair, were forming a private company, Essex Airport, Inc., to open an airport to serve Montclair. Seven miles from the town, it was near enough to reach quickly by Bloomfield Avenue without putting Montclair homes on the First Watchung Mountain at risk. A newspaper at the time noted, "The proposed establishment of an aviation field near Caldwell recalls the one that existed in Fairfield section nearby, during the war when a Naval Rifle Range was located in Caldwell Township." The new airport would be known as Marvin Field, named after, Walter Marvin, the Montclair man who had spearheaded the project.

Marvin Airport: Montclair's Role in Aviation

Labels: Aviation, Curtiss-Wright, history

Caldwell Airport,

CDW,

Curtiss Wright,

David Cannon,

Essex County Airport,

Fairfield,

Lindbergh,

Marvin Airport,

Montclair,

New Jersey,

NJ,

Spirit of St. Louis,

Tiffany

Curtiss Airports Corporation

Walter Marvin resided at 184 Upper Mountain Avenue, attended First Congregational Church, and was a former trustee of the Montclair Art Museum, a vice president of the Montclair Theater Guild, a member of the Montclair Golf Club, and on the budget committee of the Community Chest, according to a October 18, 1930 "Who's Who in Montclair" profile in The Montclair Times.

A poet and newspaper reporter as a young man, Marvin told the Times that the "'arts of communications and transportation are the greatest civilizing influences…removing fears from human life...(bringing) the remotest peoples together, closer to understanding.'" The profile also noted that his Brooklyn-born wife, Jean Murray Marvin, had been the first adult woman to make a transcontinental air trip, when she was a pioneering passenger journeying over T.A.T's "Lindbergh Air-Rail Line” from New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco.

All other Essex Airport, Inc. executives were also from Montclair: George F. Hewitt Jr.; William Osgood Morgan; Adolph J. Lins, president of the Montclair Trust Company, and Herbert E. Jefferson.

Marvin, Hewitt and Lins were also on the airport's board of directors which included: Ralph H. Bollard, member of Dillon, Reade & Company; William O. Morgan, attorney with Noble, Morgan and Scammell; Jansen Noyes of Hemphill, Noyes and Company; Roy E. Tomlinson, president of National Biscuit Company (later Nabisco); and James C. Willson, a pioneer of aviation organization and financing involved in a dozen such companies and president of National Aviation Corporation. Robert Christie and William L. Maude were to undertake the development of the airport and were instrumental in directing the $500,000 plus acquisition of the airport. Christie also was the first president of the Essex Flyers’ Club, which was chaired by Montclair’s director of the Department of Public Works, Commissioner Arthur P. Heyer, who had recommended a municipally controlled airport for Montclair in December 1928.

Both Marvin and Willson were directors of Transcontinental Air Transport Company (T.A.T. was predecessor of TWA), which at the time was in a joint partnership with the Pennsylvania Railroad to provide 48-hour air-rail service to the West Coast. The airport would also serve cross-country flyers and mail planes coming from the west whose pilots did not want to deal with the fog and smoke over the Newark meadows and Long Island.

Adjacent to the airport was the soon-to-be-constructed Passaic Avenue, a significant western part of the so-called "Metropolitan Loop Highway." Plans for this road system in the early 1930s called for it to run around New York City, crossing over the newly constructed George Washington Bridge, out Route 4 to the Fair Lawn area then looping southwest to Passaic Avenue which would eventually run over to Livingston past another airport and down to Newark. Marvin and Willson saw the Loop as a way to speed airplane passengers down to Penn Station in Newark for rapid transit into New York City.

Those two Montclair men were also directors of Curtiss Flying Service, Inc. and within a month the new airport was taken over as a wholly owned subsidiary of the newly formed Curtiss Airports Corporation, headed by C. M. Keys (on the right), a man later regarded as "The Father of American Commercial Aviation."

In 1930 Keys-Hoyt held over two dozen aviation-related companies, and years later, he also developed Peruvian International Airways and China National Aviation Corporation, which played a role in the development of the Flying Tigers American Volunteer Group prior to America’s entry into the Asian arena in World War II. Among other Curtiss Airports Corporation directors were Erle P. Halliburton founder of the company that Vice President of the United States Richard Cheney eventually presided over, and Donald Douglas who would revolutionize flight with the DC-3.

Following the takeover of the new airport facility in Fairfield, it was still to be known as Marvin Airport and to be presided over by Montclair resident Walter Marvin. At the same time, Curtiss Airports issued stock and raised over $31 million to acquire at cost thirteen fields across the country that would be used for private planes and training flyers.

It was envisioned that some 400 student flyers would train under the direction of Charles S. ("Casey") Jones, a former football coach at Montclair Academy. The Montclair Times on May 11, 1930 described Jones as a "world famous flier and former resident of Montclair." The airport's location was considered a perfect place to train because "open meadows on every side, and nearby golf courses afford many emergency landing places."

In July, 1929, the newspaper reported that Colonel Charles Lindbergh was considering purchasing a home on a North Caldwell mountain overlooking the airport, but the deal fell through, and he made his fateful move to the Hopewell Junction where his son was kidnapped and murdered.

Curtiss Airports Corporation also purchased radio station WRNY dedicating it to aviation information including events at its airports in Valley Stream, Flushing and the Fairfield section of Caldwell Township.

Labels: Aviation, Curtiss-Wright, history

C. M. Keys,

Caldwell,

China National Aviation,

Curtiss Airports,

Metropolitan Loop Highway,

Montclair Art Museum,

National Aviation,

Pennsylvania Railroad,

TAT,

Transcontinental Air,

Walter Marvin

Curtiss-Essex Airport

By the time the airport in Fairfield officially opened, it was no longer being called Marvin Airport, but instead Curtiss-Essex Airport, yet Walter Marvin of Montclair remained omnipresent. On October 29, 1930, The Montclair Times carried a front page article about the airport's opening with a photo of the dashing, six-foot-four tall Marvin whom Alex Davidson later learned from one of Marvin's daughter-in-laws had been dubbed "the most handsome man in Manhattan." The official grand opening was attended by 40,000 people, including twenty-year-old Juliet Marston of 21 Erwin Park Road, Montclair who had learned to fly solo at the field in a record five-and-a-half hours of instruction, beating the likes of Amelia Earhart, a visitor to the Marvin’s home. The previous record at the airport was eleven hours.

In July 1931, Marvin organized the Aviation Country Club of New Jersey, joining others in Boston, Philadelphia, Westchester County, and Hicksville, L.I. Many of the club members were from Montclair, more than ten of them owned planes, and it was announced that Walter L. Conwell, who lived in the town and was president of the Downtown Athletic Club of New York, had just purchased a Pitcairn Autogiro. The club utilized the Happy Landings Tea Room in North Caldwell as its headquarters, and envisioned having a pool and tennis courts that members could enjoy after flying.

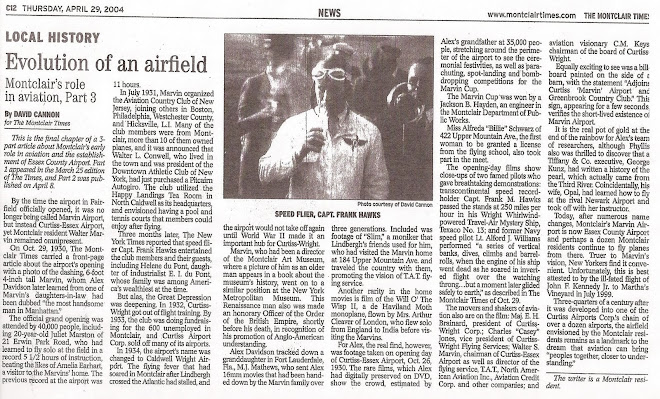

Three months later The New York Times reported that speed flier, Captain Frank Hawks, entertained the club members and their guests, including Helene du Pont, daughter of industrialist E.I. du Pont, whose family was among America's wealthiest at the time.

But alas, the Great Depression was deepening. In 1932, Curtiss-Wright got out of flight training. By 1933, the club was doing fundraising for the 600 unemployed in Montclair, and Curtiss Airport Corporation sold off many of its airports. In 1934, the airport's name was changed to Caldwell Wright Airport. The flying fever that had soared in Montclair after Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic had stalled, and the airport would not take off again until World War II made it an important hub for Curtiss-Wright.

Marvin who had been a director of the Montclair Art Museum, where a picture of him as an older man appears in a book about the museum's history, went on to a similar position at the New York Metropolitan Museum. This Renaissance man also was made an honorary Officer of the Order of the British Empire, shortly before his death, in recognition of his promotion of Anglo-American understanding.

Alex Davidson tracked down a granddaughter in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, M. J. Mathews, who sent Alex 16mm movies that had been handed down by the Marvin family over three generations. Included was footage of "Slim," a moniker that Lindbergh's friends used for him, who had visited the Marvin home at 184 Upper Mountain Avenue and traveled the country with them, promoting the vision of T.A.T.

Another rarity in the home movies is film of the Will O' The Wisp II, a de Haviland moth monoplane, flown by Mrs. Arthur Cleaver of London, who flew solo from England to India before visiting the Marvins.

For Alex, the real find, however, was footage taken on opening day of Curtiss-Essex Airport, October 26, 1930. The rare films, which Alex had digitally preserved on DVD, show the crowd, estimated by Alex's grandfather at 35,000 people, stretching around the perimeter of the airport to see the ceremonial festivities as well as parachuting, spot-landing and bomb-dropping competition for the Marvin Cup, which was won by a Jackson B. Hayden, an engineer in the Montclair Department of Public Works. Miss Alfreda "Billie" Schwarz of 422 Upper Mountain Avenue, the first woman to be granted a license from the flying school, also took part in the meet.

The opening day films show close-ups of two famed pilots who gave breathtaking demonstrations: transcontinental speed record-holder Captain Frank M. Hawks passed the stands at 250 miles per hour in his Wright Whirlwind powered Travel-Air Mystery Ship, Texaco No. 13, and former Navy speed pilot Lieutenant Alford J. Williams performed "a series of vertical banks, dives, climbs and barrel-rolls, when the engine of his ship went dead as he soared in inverted flight over the watching throng…but a moment later glided safely to earth" described The Montclair Times of October 29.

The movers and shakers of aviation also are on the film: Major E. H. Brainard, President of Curtiss-Wright Flying Service; Charles “Casey” Jones, vice president of Curtiss-Wright Corp.; Walter S. Marvin, Chairman of Curtiss-Essex Airport as well as director of the flying service, T.A.T., North American Aviation, Inc., Aviation Credit Corporation and other companies; and aviation visionary C.M. Keys, Chairman of the Board of Curtiss-Wright Corp.

Equally exciting to see was a billboard painted on the side of a barn with the statement "Adjoins Curtiss 'Marvin' Airport and Greenbrook Country Club." This sign, appearing for a few seconds, verifies the short-lived existence of Marvin Airport. It is the real pot of gold at the end of the rainbow for Alex's team of researchers, although Phyllis also was thrilled to discover that a Tiffany & Co. executive, George Kunz, had written a history of the pearl which actually came from the Third River. Coincidentally, his wife, Opal, had learned how to fly at the rival Newark Airport and took off with her instructor.

Today, after numerous name changes, Montclair's Marvin Airport is now Essex County Airport and perhaps a dozen Montclair residents continue to fly planes from there. Truer to Marvin's vision, New Yorkers find it convenient. Unfortunately, this is best attested to by the ill-fated flight of John F. Kennedy, Jr. to Martha's Vineyard in July 1999.

Three quarters of a century after it was developed into one of the Curtiss Airports Corporation's chain of over a dozen airports, the airfield envisioned by the Montclair residents remains as a landmark to the dream that aviation can bring "peoples together, closer to understanding."

Copyright 2004 David Price Cannon

In July 1931, Marvin organized the Aviation Country Club of New Jersey, joining others in Boston, Philadelphia, Westchester County, and Hicksville, L.I. Many of the club members were from Montclair, more than ten of them owned planes, and it was announced that Walter L. Conwell, who lived in the town and was president of the Downtown Athletic Club of New York, had just purchased a Pitcairn Autogiro. The club utilized the Happy Landings Tea Room in North Caldwell as its headquarters, and envisioned having a pool and tennis courts that members could enjoy after flying.

Three months later The New York Times reported that speed flier, Captain Frank Hawks, entertained the club members and their guests, including Helene du Pont, daughter of industrialist E.I. du Pont, whose family was among America's wealthiest at the time.

But alas, the Great Depression was deepening. In 1932, Curtiss-Wright got out of flight training. By 1933, the club was doing fundraising for the 600 unemployed in Montclair, and Curtiss Airport Corporation sold off many of its airports. In 1934, the airport's name was changed to Caldwell Wright Airport. The flying fever that had soared in Montclair after Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic had stalled, and the airport would not take off again until World War II made it an important hub for Curtiss-Wright.

Marvin who had been a director of the Montclair Art Museum, where a picture of him as an older man appears in a book about the museum's history, went on to a similar position at the New York Metropolitan Museum. This Renaissance man also was made an honorary Officer of the Order of the British Empire, shortly before his death, in recognition of his promotion of Anglo-American understanding.

Alex Davidson tracked down a granddaughter in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, M. J. Mathews, who sent Alex 16mm movies that had been handed down by the Marvin family over three generations. Included was footage of "Slim," a moniker that Lindbergh's friends used for him, who had visited the Marvin home at 184 Upper Mountain Avenue and traveled the country with them, promoting the vision of T.A.T.

Another rarity in the home movies is film of the Will O' The Wisp II, a de Haviland moth monoplane, flown by Mrs. Arthur Cleaver of London, who flew solo from England to India before visiting the Marvins.

For Alex, the real find, however, was footage taken on opening day of Curtiss-Essex Airport, October 26, 1930. The rare films, which Alex had digitally preserved on DVD, show the crowd, estimated by Alex's grandfather at 35,000 people, stretching around the perimeter of the airport to see the ceremonial festivities as well as parachuting, spot-landing and bomb-dropping competition for the Marvin Cup, which was won by a Jackson B. Hayden, an engineer in the Montclair Department of Public Works. Miss Alfreda "Billie" Schwarz of 422 Upper Mountain Avenue, the first woman to be granted a license from the flying school, also took part in the meet.

The opening day films show close-ups of two famed pilots who gave breathtaking demonstrations: transcontinental speed record-holder Captain Frank M. Hawks passed the stands at 250 miles per hour in his Wright Whirlwind powered Travel-Air Mystery Ship, Texaco No. 13, and former Navy speed pilot Lieutenant Alford J. Williams performed "a series of vertical banks, dives, climbs and barrel-rolls, when the engine of his ship went dead as he soared in inverted flight over the watching throng…but a moment later glided safely to earth" described The Montclair Times of October 29.

The movers and shakers of aviation also are on the film: Major E. H. Brainard, President of Curtiss-Wright Flying Service; Charles “Casey” Jones, vice president of Curtiss-Wright Corp.; Walter S. Marvin, Chairman of Curtiss-Essex Airport as well as director of the flying service, T.A.T., North American Aviation, Inc., Aviation Credit Corporation and other companies; and aviation visionary C.M. Keys, Chairman of the Board of Curtiss-Wright Corp.

Equally exciting to see was a billboard painted on the side of a barn with the statement "Adjoins Curtiss 'Marvin' Airport and Greenbrook Country Club." This sign, appearing for a few seconds, verifies the short-lived existence of Marvin Airport. It is the real pot of gold at the end of the rainbow for Alex's team of researchers, although Phyllis also was thrilled to discover that a Tiffany & Co. executive, George Kunz, had written a history of the pearl which actually came from the Third River. Coincidentally, his wife, Opal, had learned how to fly at the rival Newark Airport and took off with her instructor.

Today, after numerous name changes, Montclair's Marvin Airport is now Essex County Airport and perhaps a dozen Montclair residents continue to fly planes from there. Truer to Marvin's vision, New Yorkers find it convenient. Unfortunately, this is best attested to by the ill-fated flight of John F. Kennedy, Jr. to Martha's Vineyard in July 1999.

Three quarters of a century after it was developed into one of the Curtiss Airports Corporation's chain of over a dozen airports, the airfield envisioned by the Montclair residents remains as a landmark to the dream that aviation can bring "peoples together, closer to understanding."

Copyright 2004 David Price Cannon

Labels: Aviation, Curtiss-Wright, history

Alex Davidson,

Amelia Earhart,

Aviation,

Curtiss Wright,

Curtiss-Essex Airport,

de Haviland,

du Pont,

Frank Hawks,

John F. Kennedy Jr.,

Marvin Airport,

Montclair,

Montclair Times,

Pitcairn Autogiro

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)